By Simon Knutsson

Published October 16, 2019. Last update July 1, 2022. I started writing this text in 2017

Some in the effective altruism (EA) and existential risk circles seem to behave in problematic ways. The pattern that I think I see is that they want to have influence and therefore act in problematic and unusual ways. I bring up things that I would have wanted to be aware of if I had not already made the observations. The broad theme is acting in ways that appear one-sided, misleading, manipulative, opaque or to lack integrity, or doing things behind the scenes that seem troublesome. Not everything I list fits all these descriptions, but this is the general pattern. I perceive the behaviours as undermining and having a negative effect and corrupting influence on the research and writing landscape, public debate, and teaching.

An important point is that what I see in EA and existential risk circles look abnormal to me. For example, here are some of the troublesome-looking things that I have not seen outside of EA and existential risk circles (at least I have not seen them to nearly this extent): First, behind-the-scenes coordination, guidelines and outreach that encourage writers and researchers to mention some ideas and texts about moral philosophy and values and to keep quiet about some such ideas. This behind-the-scenes work coincides with a lot of money being granted, and neither the organisation awarding the grant or the recipient will answer my questions. Second, an organisation (the Centre for Effective Altruism, CEA) whose trustees or board members are mainly philosophers compiles a syllabus “to provide inspiration for lectures and professors” which amounts to a one-sided promotion of these philosophers’ (and a closely affiliated philosopher’s) texts and ideas to students. Third, the citation practices by some in EA and existential risk circles are problematic beyond what I have seen elsewhere. The pattern is to mention and cite ideas one agrees with, avoid mentioning competing ideas and texts, and cite one’s allies’ or colleagues’ work (maybe to promote those ideas, texts, allies and colleagues). Fourth, an Associate Professor in Philosophy at Oxford University who is also a team member of the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) at the same university and a trustee of CEA has used at least one ghostwriter. This can, but need not, be substantially problematic, depending on what was written. Fifth, another philosopher who is a Professor at Oxford University and founding Director of FHI makes a seemingly misleading and perhaps false claim on his CV (it seems no one knows whether it is false, including the philosopher himself). It may be common to exaggerate on a CV but this is at a level I have not seen before. In general, the writings I often see in these circles remind me of lobbying and political advocacy but in EA and existential risk circles, it is done by university faculty and people with PhDs and with a veneer of being scientific and open, while my impression is that it is not. If someone asked me which people in the whole world with a PhD in philosophy appear to behave in the most troublesome ways and which philosophers I trust the least, I would rank some of the philosophers in EA and existential risk circles around the top of my list.

My aim is not to attack specific people or point fingers and say ‘look at what that person did,’ which would be fairly uninteresting. I think people should be aware of what I write in this essay, be very critical of what they hear and read in EA and existential risk circles, and, importantly, scrutinise what is going on. My most important point is my call for ongoing investigations and scrutiny. A remedy to the kind of behaviour I describe is to have more scrutiny so that it is in people’s interest to avoid such behaviour, and so that the public is aware of what is going on. To be clear, I do not claim to have conclusive evidence for every seemingly problematic behaviour I bring up here. Some of the things I bring up because they appear problematic and warrant further scrutiny. I hope I provide enough of my observations and impressions to show that there is a need for ongoing scrutiny. I hope others will scrutinise more, and that some people who are aware of problematic things happening, especially behind the scenes, will speak up. However, I understand if few in EA and existential risk circles will speak publicly about problems they have observed because by doing so one may harm one’s chances of being employed or funded in this sector. Also, the philosophy world is small and, for example, by writing this text I may harm my academic career. Anyway, my key message is that some things in EA and existential risk circles seem to be highly problematic and abnormal and I hope people will be critical, scrutinise, fact check and speak in public about what goes on, especially about what goes on behind the scenes.

The reactions to what I write in this text have been mixed. Some find my points weak, that I behave badly by writing as I do, or that I give a bad impression. One philosopher didn’t have an opinion on the behind-the-scenes activities I describe. Others react with statements such as that some behaviour I describe is ‘totally unacceptable’ or ‘This is very troubling… You (or someone else) should probably post this on the EA forum.’ One philosopher thought the behind-the-scenes activities I describe sound corrupt, another thought the EA and existential risk circles sound like a sect, a third thought I seem to point to improper things and that it was good that I wrote. One person found some of the behaviours I describe ‘manipulative.’

Around 2004–2005, I recall thinking about how to have an impact. I thought that instead of becoming a medical doctor, one should work on a large scale, for example, by training medical doctors to improve a health care system. I gave to a charity project in Uganda. I was interested in information about charities’ impact, but what I had seen was mainly unhelpful numbers about how much of expenses goes to administration, fundraising and programs. In the summer of 2008, I interned for the United Nations in Stockholm, and that summer I attended a lecture by Peter Singer in Stockholm who mentioned a new project called GiveWell. In July 2008, I talked to GiveWell about volunteering for the organisation, which I started doing soon thereafter. In 2010, I became a Research Analyst at GiveWell. Elie, Holden, Natalie and I were the four staff members at the time if I recall correctly. I have a good impression of all of them. They seemed nice and genuine. Most people I have worked with in EA seem nice. A few years later, I became the chair of the board of Animal Charity Evaluators. (I have donated to GiveWell, Animal Charity Evaluators and other organisations.) I then worked as a Researcher at the Foundational Research Institute (FRI) and I was the leader of the political party for animals in Sweden. FRI works, at least partly, on risks of astronomical future suffering (s-risks). There is some but not complete overlap between s-risks and existential risks: some, but not all, s-risks are also existential risks, and vice versa. I have worked on s-risks at and outside of FRI. Now I am a PhD student in philosophy.

Problems

Troublesome work behind the scenes, including censoring research and suppressing ideas and debates

A lot seems to happen behind the scenes in EA and existential risk circles.

My perhaps most important example in this essay concerns a $1,000,000 grant by the Open Philanthropy Project and two non-public communication guidelines. I provide details right below, but here is a summary. Nick Beckstead works at the Open Philanthropy Project, has a PhD in philosophy, is a trustee of CEA, and is listed as a Research Associate at FHI’s website (FHI is a research institute at Oxford University led by Nick Bostrom). Beckstead was one of the grant investigators for the $1,000,000 grant and the author of a non-public document with communication guidelines. The grant recipient was the Effective Altruism Foundation (EAF). Managers at EAF also wrote non-public communication guidelines meant both for people employed at or funded by EAF and others including university employees like me. I understand the two documents with guidelines as a pair. For example, the guidelines by Beckstead says, “EAF has written its own set of guidelines intended for people writing about longtermism from a suffering-focused perspective.” When a manager at EAF presented the two guidelines to me, he used phrases such as a “coordinated effort” and “it means that we will promote future pessimism … to a lesser extent.” A manager at EAF also communicated that they worked on this with Beckstead who wrote guidelines in turn. The guidelines by EAF encourage the reader to not write about or promote the idea that the future will likely contain more disvalue than value. I gather from a conversation that Beckstead was involved when it comes to this part of the content in the EAF guidelines. Beckstead has defended essentially the opposite idea that if humanity may survive for many years, the expected value of the future is astronomically great.1For example, Beckstead’s dissertation “On the overwhelming importance of shaping the far future” states an argument including “2. If humanity may survive may survive [sic] for millions, billions, or trillions of years, then the expected value of the future is astronomically great,” and then says “In defense of premises 2 and 4, I argued that…” (pages 177-178). The EAF guidelines also encourage referencing Beckstead’s PhD dissertation, as well as several texts by his colleagues (at FHI and CEA) who are also philosophers. Around the time and after the two guidelines were shared with me, management at EAF did non-public outreach to encourage people to follow the guidelines. I was told essentially that I could likely get funding in the future if I would follow the guidelines. One manager at EAF also expressed a disposition to maybe silence online discussion of an argument in my paper The World Destruction Argument. This argument is, roughly speaking, against the kinds of views Beckstead has written favourably about. I think the public should be aware of these coordinated efforts behind the scenes that are partly aimed to influence which ideas about ethics and value are written about in public. That the $1,000,000 grant was made around the time the communication guidelines were shared makes the situation look even worse. A question is whether the function of the large grant was partly to silence certain pessimistic views on ethics or value. Based on a conversation with a manager at EAF, I gather the grant might not have been made if EAF did not write their guidelines. Important questions include whether there are other cases like this in which agreements have been made that include which views on morality or value to mention and not to mention and which texts to reference and whether money has changed hands in connection with such agreements. I find all this to undermine research and public intellectual debate, and to be deceptive to those who are unaware of what goes on behind the scenes. I hope future scrutiny will reveal if there have been other agreements and behaviours like this and prevent future such behaviour.

On July 18, 2019, Stefan Torges, one of the Co-Executive Directors of EAF, shared with me two communication guidelines in Google document format. One of the two documents says,

Written by Nick Beckstead with input and feedback from various community members and several EA organizations. These guidelines are endorsed by the following organizations and individuals: 80,000 Hours, CEA, CFAR, MIRI, Open Phil, Nick Bostrom, Will MacAskill, Toby Ord, Carl Shulman…. This document was originally shared with staff members at the above organizations and a handful of other individuals writing on these topics. The document is intended to be shared with individuals where it seems useful to do so, but was not intended for publication. To share the document with additional people, please request permission by emailing Bastian Stern (bastian@openphilanthropy.org).

The other document says,

Written by the Effective Altruism Foundation (EAF) and the Foundational Research Institute (Jonas Vollmer, Stefan Torges, Lukas Gloor, and David Althaus) with input and feedback from various community members and several EA organizations.

First written: March 2019; last updated: 10 September 2019.

Please ask Stefan (stefan.torges@ea-foundation.org) before sharing this document further

This is, of course, a quote from a later version updated September 10 and not the version I was shown in July, which I can no longer access and which EAF is not willing to share with me now. To be clear, I do not mean to ascribe any malicious intentions to anyone at EAF or FRI. In particular, I will mention Torges often in this section, but that is merely because he is the person I was mainly in touch with regarding these guidelines and the coordination. My impression is that he is a nice guy, wants to help others, especially those who suffer, and he thinks that this is the best way to do so. I will also mention Beckstead often, but what the Open Philanthropy Project and its funders do is more important.

The guidelines by EAF/FRI have been shared with people who do not work at EAF or FRI like me (I am employed by Stockholm University). Based on my conversation with Stefan, I understand the guidelines by EAF/FRI to be binding for those employed or funded by EAF/FRI, but they are also meant for independent researchers and university employees. The scope of the guidelines is wide. The EAF guidelines from Sep. 2019 say,

We encourage you to follow these guidelines for all forms of public communication, including personal blogs, social media, essays, books, talks, meetups, and scholarly publications.

Among other things, the guidelines by EAF/FRI encourage the reader to not write about or promote the idea that the future will likely contain more disvalue than value.2 I can no longer access the version from July 2019 I was shown and EAF will not share it. I only have a version from September 2019, which I gather was revised after I criticised the version from July. The September version may have softened the language and edited some of the most problematic formulations. I here quote some important passages from different places in the version last updated Sep. 10, 2019 (those behind the guidelines could make the whole documents public, including earlier versions closer in time to the grant by the Open Philanthropy Project): “…we would like to avoid (inadvertently) contributing to strong forms of future pessimism…. People holding the following set of beliefs (NNT) are particularly likely to engage in harmful behavior: (1) Negative Future. Given the current trajectory of human civilization, the future will likely contain more disvalue than value…. We can avoid inadvertently increasing the number of actors who hold this set of beliefs by reducing advocacy for (1)…. we think promoting (parts of) the NNT belief combination would be uncooperative…. In general, we recommend writing about practical ways to reduce s-risk without mentioning how the future could be bad overall…. If you’re set on discussing more fundamental questions despite the arguments and concerns outlined above, we encourage you to go beyond academic norms to include some of the best arguments against these positions, and, if appropriate, mention the wide acceptance of these arguments in the effective altruism community…. Consider acknowledging that there are other ways of positively shaping on [sic] the long-term future beside reducing s-risks: reducing extinction risks and ensuring a flourishing future.” The guidelines by EAF/FRI also lists literature that the reader may want to reference, including Beckstead’s PhD dissertation, and texts by Carl, William, and Bostrom. The guidelines also encourage the reader to mention and emphasise various ideas. For example, the EAF guidelines say,

For normative questions, you could consider referencing Beckstead: On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future, Pummer: The Worseness of Nonexistence, or Shulman: Moments of Bliss for alternative views. Consider emphasizing normative uncertainty (or the anti-realist equivalent of valuing further reflection), e.g. by referencing Bostrom (2009): Moral uncertainty – towards a solution?, EA Concepts: Moral uncertainty, MacAskill (2014): Normative uncertainty, Greaves & Ord: Moral uncertainty about population axiology. [Links to texts got lost when pasting.]

Several of these authors whose texts the reader is encouraged to reference either wrote or endorsed the other guidelines (Beckstead, Bostrom, MacAskill, Ord, and Shulman), and almost all of the authors are listed online as colleagues of Beckstead. Beckstead, Bostrom, Greaves, MacAskill, Ord, and Shulman are listed on the FHI team page. Beckstead, Greaves, MacAskill, and Ord are listed as trustees or board members of CEA.

I spoke with Stefan and wrote to him, David, Jonas and Lukas, and criticised the guidelines and the whole deal. On July 29, I proposed that I be removed from the FRI website, which I have been now, and I am no longer affiliated with EAF or FRI. The same month, in July 2019, EAF was awarded $1,000,000 by the Open Philanthropy Project (whose website says , “Our main funders are Cari Tuna and Dustin Moskovitz, a co-founder of Facebook and Asana”). The grant web page says “Grant investigators: Nick Beckstead and Claire Zabel.” Claire Zabel is also a trustee of CEA.

I am also troubled by what influence those behind the guidelines have had and will have by direct communication with researchers and others about what to say or publish. A while back, I mentioned to Stefan Torges a seminar with a philosophy professor. The seminar was titled Pessimism about the Future, and the abstract on the web page says,

It is widely believed that one of the main reasons we should seek to decrease existential risk arising from global warming, bioterrorism, and so on is that it would be very bad overall were human and other sentient beings to become extinct. In this presentation, I shall argue that it is not unreasonable to believe that extinction would be good overall.

Stefan then reached out to the professor, which may be problematic. I do not know what Stefan said or tried to say to the professor. It would be fine if he said roughly “beware of how you write so that no extremists try to kill a lot of people.” But I worry that in this case or future cases, those behind the guidelines will reach out to those who write about pessimism and related topics in ethics to try to silence them or see to that they edit their work so that it is more in line with what Beckstead would like to see published or said in public.

Another such case relates to a post on the EA forum on September 6, 2019. The post asks ‘How do most utilitarians feel about “replacement” thought experiments?’ The post quotes my paper The World Destruction Argument. In that paper, I challenge moral views of the kind that Beckstead, MacAskill, Ord and Bostrom seem to hold. Jonas Vollmer wrote me and said he spoke with the poster one or few days before the post was published, and that Jonas might have discouraged the poster from making the post if the poster had used a “world destruction” framing. In other words, the organisation where Jonas is Co-Executive Director receives 1 million in a grant for which Beckstead is a grant investigator, and then Jonas may discourage public discussion of my academic work that challenges moral views similar to Beckstead’s.

Similarly, Torges wrote me on July 26, 2019, wondering if I had considered changing the title and/or abstract of my paper on the world destruction argument, which had recently been accepted for publication in a journal. He said he would be happy to help with this. I said no and that I react negatively to his question.3More exactly, a part of my reply reads, “I don’t think I will want to change after hearing your suggestion, assuming your suggestion will be in the spirit of the guidelines. And I doubt I can change it now. The paper is at copy-editing and typesetting stage at the publisher so I predict changing title or abstract would be difficult. I react negatively to your question.” Torges did not pursue his question. Actually, someone else also suggested that I make a change after the paper had been accepted, but I didn’t perceive that as especially problematic. When Stefan wrote to me, the circumstances make it seem like it was not just a friendly improvement suggestion. I mean, Stefan and others had just made an agreement with Beckstead, who was a grant investigator for a recent large grant to Torges’ organisation. I think Beckstead would like to see my paper not published at all or at least edited in certain ways. And then it seems like Stefan carried out that work of trying to influence this publication. That’s what I don’t like. It is fine for people, in general, to give improvement suggestions at any stage of a paper.

A problem with the communication guidelines and behaviours just described is that they go against scientific ideals about freedom to pursue ideas and about pitting ideas against one another. The situation in effective altruism and existential risk circles seems to rather be that some people use power, money, resources and connections in troublesome ways to promote themselves and their ideas and values.

On Oct. 31 and Nov. 5, 2019, I wrote questions to the Open Philanthropy Project, including

- Has the Open Philanthropy Project recommended a grant and, without saying so in public, conditioned the grant on the following or encouraged the grant recipient to do the following: not publicly endorse or not publicly write favourably about the ideas that the future will be bad overall or likely contain more disvalue than value?

- Was the grant to EAF explicitly or implicitly conditioned on EAF writing guidelines and/or distributing them?

- Did Beckstead or someone else at the Open Philanthropy Project communicate to anyone at EAF that a grant would be more likely or larger if EAF wrote guidelines?

- I wonder whether Beckstead influenced or tried to influence what Jonas Vollmer, Stefan Torges, Lukas Gloor, and David Althaus wrote in their guidelines, or the fact that they wrote guidelines at all. If so, was any such activity by Beckstead a part of his work for the Open Philanthropy Project, or was he, for example, acting only as a private person?

I also asked whether I may share the replies in public. A person at the Open Philanthropy Project replied that they do not have anything to add beyond the grant page, which does not answer my questions. I also wrote similar questions to Stefan Torges, one of the Co-Executive Directors of EAF, on Nov. 2 and 5, 2019, including the following questions:

- Did Nick Beckstead express a wish that the guidelines encourage referencing his PhD dissertation?

- Did he edit the document [with the EAF the guidelines] or make comments in it?

- Did the Open Philanthropy Project condition the grant to EAF on the following or encourage EAF to do the following: not publicly endorse or not publicly write favourably about the ideas that the future will be bad overall or likely contain more disvalue than value?

- May I share my questions and your replies in public?

Stefan Torges replied on Nov. 4 and 7, 2019, with no answers to any of my questions and essentially saying that they will not reply to my questions (see this page for essentially our entire exchange). I tried to contact Nick Beckstead but I did not find any contact information online. Later, on 2 Jan. 2020, I wrote Beckstead on Messenger and LinkedIn (we are 1st-degree connections on LinkedIn), but as of 29 Jan. 2020 I do not see any reply.

According to the website of the Open Philanthropy Project, “Openness is a core value of the Open Philanthropy Project…. We believe philanthropy could have a greater impact by sharing more information. Very often, key discussions and decisions happen behind closed doors…”

EAF writes on its website that “Effective Altruism Foundation (EAF) strives for full transparency.” These organisations appear to go against their own statements about openness or transparency given their activities and reluctance to answer questions.

I think those who help these organisations with donations, work, or promotion should demand replies to the kind of questions I have asked and demand that they be open about the activities I describe.

The guidelines written by Beckstead say they are endorsed by 80,000 Hours, CEA, CFAR, MIRI, Open Phil, Nick Bostrom, Will MacAskill, Toby Ord, and Carl Shulman. One may ask about all of these organisations and individuals how and to what extent they were involved in the deal. For example, why did they endorse the guidelines? Did they influence the formulation of the EAF guidelines? Were they aware that EAF also wrote and would distribute guidelines (behind the scenes) that encourage readers to not publicly endorse or not publicly write favourably about the ideas that the future will be bad overall or likely contain more disvalue than value? Did they know or encourage that the EAF guidelines encourage referencing texts by these authors? For example, when Torges shared both documents with guidelines with me on July 18, 2019, he wrote the following in the same message right below the links to two the documents:

We’re excited about this coordinated effort. Even though it means that we will promote future pessimism and s-risks to a lesser extent, we think the discourse about these topics will still be improved due to other more widely-read texts taking our perspective into account more. We already saw some concrete steps in this direction: For example, we’ve been able to give input on key 80k content and Toby Ord’s upcoming book on x-risk, which are and will be among the most widely read EA-related resources on long-termism. There will be more such content in the future, and we’ll continue to give input. Nick also invited a number of people to the research retreat that we hosted in May. All of that makes us confident that this will be a win-win outcome.

And on July 26, 2019, Torges wrote to me,

I also wanted to check back regarding our communication with Nick. Is it okay if I told him that you don’t feel comfortable endorsing the guidelines because of your current position as an academic, similar to GPI’s reservations?

A part of my reply from the same day was,

It is okay that you tell Nick that a part of the reason why I don’t endorse the guidelines is that I don’t feel comfortable endorsing the guidelines because of my current position as an academic.

I had many reasons for not endorsing the guidelines, and one of them was that I do not think a university employee should do so. I presume the Nick we were talking about is Nick Beckstead. One can wonder why Torges would be telling Nick about whether I, a PhD student in practical philosophy in Stockholm, endorse the guidelines, which, among other things, essentially encourage the reader to stay silent about an idea about value that Nick Beckstead seems opposed to, and that encourage referencing texts by Beckstead and his colleagues? One can guess based on this that Nick had an interest in knowing whether people like me endorse the guidelines (at least Torges seemed to think so).

The official justification for the guidelines and the related cooperation or agreement by some of those involved would presumably be that they worry that talking about the future being bad or pessimistic ethics may cause some extremist to kill people. I do not believe this is the whole story for several reasons. First, Beckstead, MacAskill, Ord and Bostrom have done a lot to promote views like traditional consequentialism and utilitarianism, and Ord has written, “I am very sympathetic towards Utilitarianism, carefully construed.” One can also accuse them of contributing to what one might call far-future fanaticism, according to which what happens nowadays, even violence and suffering, is essentially negligible as long as the far-future is very good. So I do not find it credible that they are so worried about talk of ethics or value leading to killings. More likely they have several other motives including that they are worried about the specific kind of killing that would prevent the existence of vast numbers of beings and purported value in the far future (killing everyone to replace them might even be morally obligatory, according to the moral views they promote). The following is some background. A standard objection to utilitarianism and consequentialism is that they imply that it would be right to kill if doing so would lead to the best results. Classical utilitarian Torbjörn Tännsjö thinks that a doctor ought to kill one healthy patient to give her organs to five other patients who need them to survive if there are no bad side effects. Philosopher Dale Jamieson wrote as early as 1984 that

many philosophers have rejected TU [total utilitarianism] because it seems vulnerable to the Replacement Argument and the Repugnant Conclusion.… The Replacement Argument purports to show that a utilitarian cannot object to painlessly killing everyone now alive, so long as they are replaced with equally happy people who would not otherwise have lived.

Tännsjö writes (my translation), “Suppose that we really can replace humans with beings who are … I think that it is clear that this is what in this situation should happen.… Let us rejoice with all those who one day hopefully … will take our place in the universe.” (For sources, see my web page). Years ago a young effective altruist asked me for career advice. The person self-identified as a classical utilitarian and the person’s goal was a hedonic shockwave, which I gather would fill the reachable part of the universe with pleasure. I don’t know if the person pictured that Earth would be destroyed in the process. The moral advocacy by Beckstead, William, Toby and Bostrom may already have resulted in violence and killings because people who are very concerned about ensuring that the far future has much value in it seem to be more prone to eat animals or animal products. A reason why they seem more prone to eat animal products is plausibly that they think the suffering and death they thereby cause is negligible compared to the vast value that could be created in the future, so they prioritise trying to make such a future more likely.

Second, if Beckstead had the power to influence the grant to EAF, he may have seen it as an opportunity to make some people at EAF write and spread communication guidelines to silence people and affect what people say so that Beckestead’s own ethical views and priorities get more widespread, while suppressing ethical views and values that compete with his own. He and others behind the guidelines may exaggerate their worry that, for example, what I write will lead to some extremist killing people, in order to get EAF to write and disseminate their guidelines. This point can also be made about the Open Philanthropy Project as an organisation, rather than merely Beckstead as an individual.

The following is an older, related example of potentially problematic behaviour behind the scenes. If I recall correctly, some years ago, Lukas Gloor and William MacAskill talked about the ethics of effective altruists. Roughly, speaking Gloor’s moral view appears pessimistic and MacAskill’s appears optimistic. They discussed a compromise (roughly a middle position), according to which effective altruists would have a moral view of the kind that suffering is twice as morally important as happiness (or, e.g., three times as important; I don’t recall exactly). I do not know if any agreement was reached or if they just discussed the idea. In any case, I do not think one should make such agreements behind the scenes.

Systematically problematic syllabi, reading lists, citations, writings, etc.

The activities described in the previous section seem to be just another instance of a pattern that has been going on for years involving to a large extent the same people and organisations, although not every person or organisation mentioned so far. Historically, a large part of the leadership of the two closely affiliated organisations CEA and FHI have been philosophy PhDs with a specific group of similar moral views, according to which, roughly speaking, it is overwhelmingly important to ensure that there will be vast amounts of value in the future. People at and around CEA and FHI seem to try to present to the public and students the part of the ethics literature that fits their specific view about the importance of ensuring the existence of very many beings and a lot of value in the future. They tend to avoid mentioning other views, and to cite and refer the reader to a small number of authors, often themselves and their colleagues, who essentially all agree with them. Another method appears to be for a philosopher at Oxford University and CEA with a PhD to write an attack on a competing view in a way that is so biased and misleading that I do not recall seeing such problematic writing in ethics by an academic philosopher outside of this cluster of people at and around CEA and FHI. Importantly, many of these texts are not directed at professional philosophers who know about other views and can immediately tell how one-sided the texts are, but the texts seem to be about convincing non-philosophers, often students and young people. All this seems to be done in different troublesome ways, which I describe below.

It seems to partly be done through trying to create syllabi with writings by themselves and those who agree with them and trying to establish such courses at universities. Perhaps the overall strategy is to influence the values of students, increase the citation count and prominence of one’s own researchers and allies, while avoid mentioning opposing views. The EA syllabi I’ve read are so one-sided that I would feel dishonest to teach a course with such a syllabus. For example, one syllabus which says it is compiled by CEA (quote from Nov. 2, 2019):

…this course syllabus, compiled by the Centre for Effective Altruism. The aim of this syllabus is not to give detailed instructions for how to run a course, but rather to provide inspiration for lectures and professors with an interest in teaching effective altruism. This syllabus is primarily intended to be used in courses in philosophy or political theory, but could also be given, in part or wholly, in courses in other subjects.

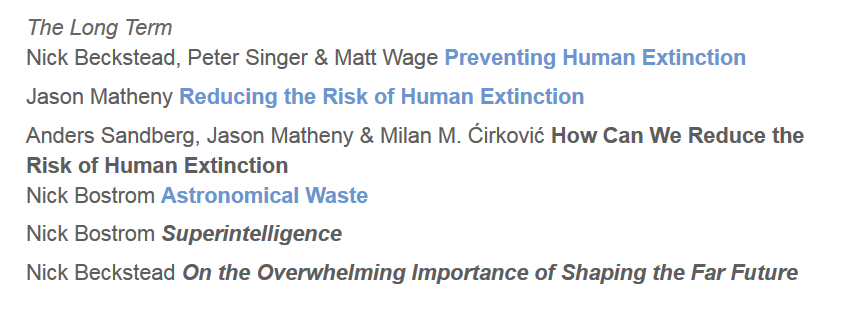

The syllabus includes the following section:

10) The far future and existential risk

Many effective altruists think that the lives of future people are highly ethically significant. A natural conclusion from that view is to focus one’s efforts on shaping the far future and, in particular, to reduce the risk of human extinction, posed by, e.g. synthetic biology and artificial intelligence. This module treats a number of themes related to these issues, from population ethics to strategies to reduce existential risk.

Beckstead, Nicholas. On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future. Ph.D Thesis, Rutgers University. (Especially ch. 1.)

Bostrom, Nick (2013). Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority. Global Policy, 4, pp. 15-31.

Bostrom, Nick (2002). Astronomical Waste: the Opportunity Cost of Delayed Technological Development. Utilitas 15, pp. 308-314.

Greaves, Hilary. Population Axiology. (Unpublished survey manuscript.)

Matheny, Jason Gaverick (2007). Reducing the Risk of Human Extinction. Risk Analysis, 27, pp. 1335-1344.

Ord, Toby (2014). The Timing of Labour Aimed at Reducing Existential Risk. Blog post at Future of Humanity Institute.

Rees, Martin (2015). This Crime Against Future Generations. The Times, 15 August 2015.

All texts listed essentially agree on the ethics. Well, Greaves’ text is as an introduction to population axiology so it is not about defending a view, but it still excludes pessimistic publications on population ethics/axiology like works by professors David Benatar, Christoph Fehige and Clark Wolf. Half of the texts are by CEA trustees (Beckstead, Greaves and Ord). Bostrom leads FHI and Matheny lists FHI as a past affiliation on his CV.

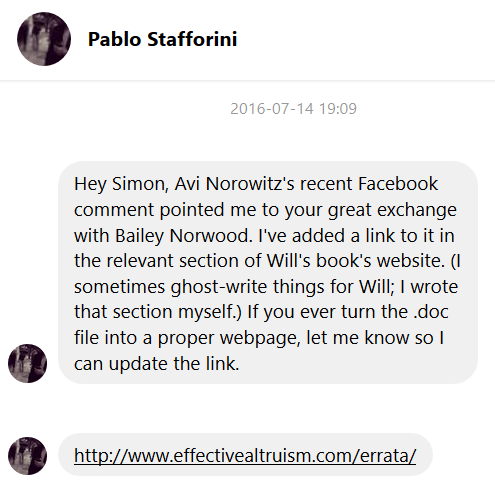

According to CEA’s organisation chart in a post from 2017, Pablo Stafforini was one of the people located directly below William MacAskill. In September 2016, Stafforini wrote in an e-mail that Will asked him to create a list of EA readings for a wealthy philanthropist, and after doing that Stafforini decided to expand it (here is the perhaps now broken link to the list). Pablo explained kindly that he felt GiveWell was overrepresented and EAF underrepresented so he asked for feedback before making it public and sharing it in the public Facebook EA group. As usual, the section on the long-term future, which I paste right below, was one-sided and referred only to people who agree and who are mainly at or around CEA and FHI (Sandberg is also a team member at FHI).

I replied that Pablo should at least add Brian Tomasik’s https://foundational-research.org/risks-of-astronomical-future-suffering/ in this section. He replied that he added it, but when I checked later and then even later in March 2018 I did not see it. I am not saying Pablo removed it, but I did not see it so someone may have.

The organisation 80,000 Hours, where MacAskill is President, is a part of CEA. The essay “Presenting the long-term value thesis” from late 2017 by Benjamin Todd, the CEO and co-founder of 80,000 Hours, was shared in the main Facebook EA group by Robert Wiblin, who works for 80,000 Hours. I agree with then philosophy PhD student Michael Plant’s comment,

I found this woefully one-sided and uncharitable towards person-affecting views (i.e. the view we should ‘make people happy, not make happy people’). I would honestly have expected a better quality of argument from effective altruists…. 1. Your ‘summary of the debate’ was entirely philosophers who all agree with your view. This is poor academic form.

A one-sided part of the essay is that the further reading section at the end only lists texts by or podcasts with Bostrom, Beckstead and Ord, i.e., two trustees of CEA and Bostrom who leads FHI which 80,000 Hours is affiliated with. They all agree, and none of the other views out there is mentioned. Another problem is that Benjamin claims to be arguing for a broad thesis about the importance of the future, but actually argues for a specific version of that view that he and all the people just mentioned at CEA and FHI seemingly endorse (see my comment).

Ord is a trustee at CEA and part of the team at FHI. His 2013 essay against negative utilitarianism (NU) is a one-sided and misleading attempt to convince lay people away from negative utilitarianism. I try to be polite in my response to it, but I will try to be blunter here. His text is so bad partly for the following reasons: Toby writes in the role of a university researcher with a PhD in philosophy, and he writes for non-experts. He spends the whole essay essentially trashing a moral view that is opposite to his own. He does little to refer the reader to more information, especially information that contradicts what he writes. He describes the academic literature incorrectly in a way that benefits his case. He writes that “A thorough going Negative Utilitarian would support the destruction of the world (even by violent means)” without mentioning that for many years, a published objection to his favoured view (classical utilitarianism) is that it implies that one should kill everyone and replace us, if one could thereby maximize the sum of well-being (see my paper The World Destruction Argument). Ord’s text fits very well with the overall pattern I describe, and the moral theory NU that Ord attacks is a typical example of the kind of view that the guidelines from 2019 mentioned above encourage the reader to not advocate or write favourably about.

In CEA’s Effective Altruism Handbook, 2nd ed. (2017), there is a chapter titled “The Long-Term Future” by Jess Whittlestone, who seemingly has interned for 80,000 Hours, which is a part of CEA. That chapter also contains one-sided framings, citations, objections, etc. (e.g., the ethics discussion on p. 76.) The only text besides Whittlestone’s in “The Long-Term Future”-part of the EA handbook is Beckstead’s “A Proposed Adjustment to the Astronomical Waste Argument.” The decision to make these two texts make up the “The Long-Term Future” part of the book is one-sided.

Let’s turn to the text Farquhar et al. (2017) “Existential Risk Diplomacy and Governance,” by the Global Priorities Project, which is or was a part of CEA. The FHI logo is also on the publication. It has a section “1.2. The ethics of existential risk,” which starts with Parfit’s (1984) idea about the importance of a populated future. Then it cites only papers by Bostrom and Beckstead, who are both affiliated with the same organisations as the authors when it makes the case that “because the value of preventing existential catastrophe is so vast, even a tiny probability of prevention has huge expected value.67” It then admirably acknowledges that there is disagreement about this:

Of course, there is persisting reasonable disagreement about ethics and there are a number of ways one might resist this conclusion.68 Therefore, it would be unjustified to be overconfident in Parfit and Bostrom’s argument.

But where do they point the reader to in note 68? Only to Beckstead’s dissertation, which argues, sometimes uncharitably, for the ethical view Bostrom and Farquhar et al. favour.

A 2017 paper by two authors from FHI called “Existential Risk and Cost-Effective Biosecurity“ was published in the journal Health Security. The paper has a section “How Bad Would Human Extinction Be?“ which has a one-sided and dubious take on the literature:

Human extinction would not only end the 7 billion lives in our current generation, but also cause the loss of all future generations to come. To calculate the humanitarian cost associated with such a catastrophe, one must therefore include the welfare of these future generations. While some have argued that future generations ought to be excluded or discounted when considering ethical actions,50 most of the in-depth philosophical work around the topic has concluded that future generations should not be given less inherent value.51-55 Therefore, for our calculations, we include future lives in our cost-effectiveness estimate.

The references in this passage are by Parfit, an Oxford philosopher who was broadly in line with FHI’s ethics; Ng, a classical utilitarian; Beckstead; Broome, an Oxford philosopher who seems to have an optimistic moral philosophy; Cowen; and a science paper by Lenton and von Bloh, which does not seem especially related to the value of future generations. As further reading, the authors point to the text by Matheny mentioned in syllabus above. As mentioned, Matheny has been affiliated with FHI. No mention of opposing views or the many philosophers who have done in-depth work arguing against the authors’ view here (see, e.g., Wikipedia entry on the Asymmetry or my essay).

By the way, this publication Matheny (2007) “Reducing the Risk of Human Extinction” that people at CEA and FHI keep pointing to is also one-sided and inaccurate in a biased way. Section 5 is about discounting and touches on population ethics. See, for example, the problematic first paragraph of the section, which gives an inaccurate picture of the state of the philosophical debate in a way that favours his view. See also the one-sided reasoning and references in note 6, which include traditional utilitarians Hare and Ng, Holtug who has argued against the Asymmetry in population ethics, and Sikora who presents an argument for classical utilitarianism. In the end, Matheny acknowledges, among others, Nick Bostrom and Carl Shulman for comments on an earlier draft.

Potentially dishonest self-promotion

On MacAskill’s profiles at ted.com and theguardian.com, and on the cover of his book Doing Good Better it says “cofounder of the effective altruism movement.” But unless I have missed some key information, he is not a cofounder of effective altruism or the effective altruism movement. When I volunteered for GiveWell in 2008–2009, the ideas of being altruistic and having an impact effectively were already established and there was a community or movement around GiveWell. Then Giving What We Can launched in November 2009. From the time I worked for GiveWell in 2010, I recall MacAskill (last name Crouch at the time) as a student who commented on the GiveWell blog. Then, in 2011, CEA was founded. Perhaps he and others started using the phrase ‘effective altruism’ but it does not really matter because using a potentially new phrase for something that already exists does not make someone a cofounder. My impression of MacAskill’s role over the years is that he has done a lot to grow the effective altruist community, movement and brand (and maybe was one of those who created the brand; I don’t know), and has spread related ideas. He has perhaps also contributed with new ideas. Importantly, he and his colleagues mentioned above, especially at CEA and Oxford University, also seem to have systematically put in a lot of effort to enter and try to shape this movement or community so that people and organisations in it share their particular moral views and priorities, and, for example, donate to the kind of activities they want to see funded (to a substantial extent because of their specific and controversial moral views).

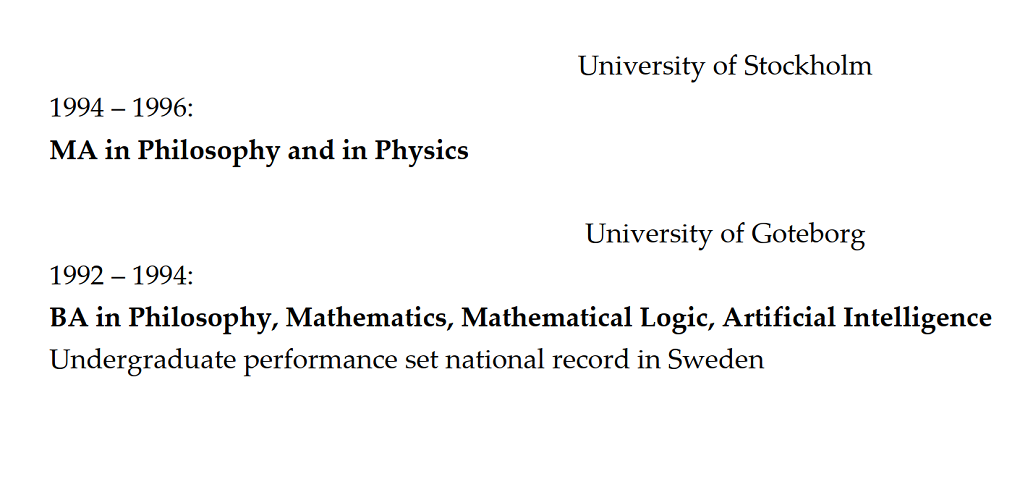

Nick Bostrom’s CV says he set a national record for undergraduate performance in Sweden, but I doubt he set such a record (I think no one knows, including Bostrom himself), and I think he presents the situation in a misleading way. His CV says,

He also used to bring up the purported record at the landing page of his website (current link https://nickbostrom.com/old/). I have a bachelor’s and two master’s degrees from the same university in Gothenburg, Sweden, and I have lived almost all of my life in Sweden. I have never heard of any national record related to undergraduate performance. I mentioned his statement ‘Undergraduate performance set national record in Sweden’ to a few people in Sweden who are familiar with the university system in Sweden. One person laughed out loud, another found his claim amusing, and a third found it weird. I called the University of Gothenburg on Oct. 21, 2019, but the person there was not aware of any such records. On Oct. 21, 2019, I wrote Bostrom and asked him about his record. On Oct. 23, 2019, he replied and gave me permission to share his reply in public, the relevant part of which reads as follows:

The record in question refers to the number of courses simultaneously pursued at one point during my undergraduate studies, which – if memory serves, which it might not since it is more than 25 years ago – was the equivalent of about three and a half programs of full time study, I think 74 ’study points’. (I also studied briefly at Umea Univ during the same two-year period I was enrolled in Gothenburg.) The basis for thinking this might be a record is simply that at the time I asked around in some circles of other ambitious students, and the next highest course load anybody had heard of was sufficiently lower than what I was taking that I thought statistically it looked like it was likely a record.

A part of my e-mail reply to Bostrom on Oct. 24, 2019:

My impression is that it may be difficult to confirm that no one else had done what you did. One would need to check what a vast number of students did at different universities potentially over many years. I don’t even know if that data is accessible before the 1990s, and to search all that data could be an enormous task. My picture of the situation is as follows: You pursued unusually many courses at some point in time during your undergraduate studies. You asked some students and the next highest course load anyone of them had heard of was sufficiently lower. You didn’t and don’t know whether anyone had done what you did before. (I do not know either; we can make guesses about whether someone else had done what you did, but that would be speculation.) Then you claim on your CV “Undergraduate performance set national record in Sweden.” I am puzzled by how you can think that is an honest and accurate claim. Will you change your CV so that you no longer claim that you set a record?

Information about university studies seems publicly available in Sweden. When I called the University of Gothenburg on Oct. 21, 2019, the person there said they have the following information for Niklas Boström, born 10 March 1973: Two degrees in total (one bachelor’s and one master’s degree). The bachelor’s degree (Swedish: fil. kand.) from University of Gothenburg was awarded in January 1995. Coursework included theoretical philosophy. The master’s degree (Swedish: magister or fil. mag.) is from Stockholm University, and, according to my notes from the call, in theoretical philosophy (although I guess coursework in some other subject could perhaps be included in the degree). He also did some additional coursework. He started to study at university in Lund in fall 1992. I asked Bostrom whether this is him but he did not reply. More information that I noted from my call with the university include that the person could see information from different universities in Sweden, and there are in total 367.5 higher education credits in the system (from different Swedish universities) for Boström, according to the current method for counting credits. 60 credits is a normal academic year (assuming one does not, e.g., take summer courses). Boström bachelor’s degree corresponds to 180 credits, which is the exact requirement for a bachelor’s degree. The total number of credits (367.5) corresponds to 6.125 years of full-time study (again, assuming, e.g., no summer courses or extra evening courses). According to the university, he started studying in 1992 and, according to Bostrom’s CV, he studied at Stockholm University until 1996. I asked Bostrom and I gather he confirmed that he only has one bachelor’s degree.

Ghostwriting

Finally, a less important point. William MacAskill is listed as the only author of the book Doing Good Better but I read the following message, which Pablo Stafforini wrote to me on Messenger, as that Stafforini wrote a part of it and that he sometimes ghost-writes for William. I agree, however, that one can reasonably read it as that Pablo ghost-writes for William but that he did not write any part of the book except a part of the errata.

One should in general not share personal communication, but I think it can be best to do so in some special cases, such as if one is calling out potential corruption or other seriously problematic behaviour. Given everything I write in this essay, I think these messages by Stafforini fit that situation.

What Pablo writes looks problematic. One reason is that I do not think an academic like William should list himself as the only author if someone else wrote parts of the book. I have many questions. For example, which parts, if any, of the book were written by people other than William? Was Pablo or anyone else who may have ghost-written for William paid by CEA? At least Pablo has worked for CEA and William is a trustee there. If William donated money to CEA, got tax deductions for that, and then made money from any texts Pablo or others at CEA ghost-wrote, that might be legally problematic. In general, which texts, where William is listed as an author, have been written by others? Update Oct. 16, 2019: Pablo replies,

in the message I sent you I was referring to ghost-writing in the context of the website, and the ‘errata’ section in particular. The ghost-writing I did for Will was restricted to stuff on the website and to drafting some private correspondence. I didn’t write any part of Will’s book, any part of any paper of his, or any part of any other published work of his.

It is good that Pablo replied. I would still be interested in which of William’s texts have been ghost-written by Pablo or others, and I think past and future ghost-writing in these circles is something that should be scrutinised.

The above list of problems in effective altruism and existential risk circles are merely some things I have noticed. I have not done any investigation to actively try to find problematic behaviour. Such an investigation would likely find more.

Writing this text

One may think that I should first or only bring up what I write here in non-public channels with those I write about, but a part of the problem is that I do not expect an honest conversation with many of them. I expect them to mainly try to maneuver the situation in a way that is in their interest, and perhaps also try to cause problems for me. In addition, I started writing this text in 2017, and in 2018 I shared an earlier and substantially different version with some of those I criticise here, including the authors of the EAF/FRI guidelines. Maybe some of my criticism of the behaviour of people like Toby Ord was shared with him and others in 2018 too, but I am not sure. I also think that what I write here should be public information.

In response to the first public version of this text, one person mentioned that it is important to research one’s accusations if one makes them in public. Another person asked why I would write, without first asking Bostrom for details, that I doubt he set the record he claims in his CV. Those are good points. Here are my two replies to why I did not ask people or do more research before writing in public.

(1) I am concerned about my safety. This point has several aspects. First, regardless of this essay, I am concerned about my safety because of the things I write and say. I indicated above what people are willing to do to try to prevent pessimistic writings like mine on ethics and the future from being published or discussed. This is non-violent, but a question is whether someone would be prepared to resort to violence. To be clear, I am, of course, not worried that any of the people I mention by name in this text would personally kill me. An example of a philosopher who appears to have been at risk is, if I recall correctly, a philosopher who had bodyguards 24 hours per day. My understanding is that this was not the philosopher being paranoid and paying for the bodyguards but the bodyguards were paid for by the university, the authorities or the like. And a philosopher posed a threat of lethal violence to me, so I took extra safety measures for a while. In addition, death threats are common in politics. For example, when I worked for a political party, I got an e-mail about strangling me slowly. That person has been described as the kind of person who would show up at your house to burn it down. Nowadays when I am no longer involved in politics, I am most concerned about someone who finds it extremely important that there will be vast amounts of positive value in the future and who believes I stand in the way of that. It is not like I am scared all the time and I still live a normal life, but I am sufficiently concerned about this risk that I take some precautions. This may sound exaggerated and like me being paranoid, but that is my take on the situation, and I do not have a history of thinking that people are out to get me. I also think I have heard about influential people in EA and existential risk circles talk about the risk of assassinations and maybe take some safety measures, so, assuming that is correct, I do not appear to be the only one who is concerned about my safety. A reflection on my experience in politics compared to my current situation is that when I worked in politics, the few people who stood out as seeming potentially dangerous looked angry, unstable and stereotypically irrational. In contrast, among some in EA and existential risk circles, my impression is that there is an unusual tendency to think that killing and violence can be morally right in various situations, and the people I have met and the statements I have seen in these circles appearing to be reasons for concern are more of a principled, dedicated, goal-oriented, chilling, analytical kind. Second, it seems like a bad idea to sit quietly on information that looks damaging if it became public. It seems safer to just make the information public so that there is less of a need to silence me. I did not know how people would react to the information in this text, and it seems to vary a lot. Third, if, before publishing this essay, I would have reached out to people and asked critical questions, asked to share publicly parts of non-public writings for the purpose of my work on a critical public piece, and so on, then a buzz might have been created about me working on this potentially damaging text. That buzz may have reached the wrong person and me working on this text would just be an extra reason to silence me from the perspective of that person. So, again, it seems safer to make my text public without delay. Fourth, for similar reasons, if I would do even more serious background research and start acting like some investigative journalist, that would perhaps increase the risk more. Simply one more reason to try to make me stop and be quiet, and I feel concerned enough about my safety as it is. Finally, a point of publicly announcing my safety concern is that it may help deter a potentially violent person because there is now more of a spotlight on the issue.

(2) The issue with Bostrom’s CV is a minor thing compared to the other things I write about in this text. It is barely worth bringing up, but I still mention it because it is one data point and a small piece of a broader pattern of behaviours. There are many people I mention in this text who I could have asked about more important things before publishing this text. But I doubt I would have time for that work, so I prefer to write based on the information I have and sometimes write in a hedged way using phrases such as ‘I doubt’ and ‘I suspect,’ and when I am more confident I write ‘this person did X.’ I partly raise the issues I do as examples of problematic or seemingly problematic things I have noted that warrant further scrutiny. These are merely things I have come across and there may be much more that I am unaware of. A fair objection to what I do is that one should either do something like this properly or not at all. So, either do not write about some of the things at all, or ask people for comments before writing in public, include their replies, do more research, ask for permission to share information about documents that are not for sharing or personal communication, perhaps also write less poorly, and so on. But then I might never have written this essay at all, which I think would have been unfortunate. So I think the bar for these kinds of writings is lower in terms of how much background work is required, as long as one is clear about that what one says is one’s impression or suspicion or the like. When I first posted Stafforini’s messages in which he says he sometimes ghost-write things for Will, I made a mistake by also writing that Stafforini wrote me that he wrote a part of the book Doing Good Better, but his message to me could reasonable be read in another way (as that he ghost-writes for Will but that he did not write any part of the book except a part of the errata). I am sorry about writing that. Finally, if I were to ask some of the people whose behaviour I criticise for details, I do not think I could take their replies at face value. So just asking them would not settle the issues, but the replies would need to be checked, perhaps followed-up on and that further information should perhaps also be integrated into the text. That would also be time-consuming.

What to do

I think there needs to be more ongoing scrutiny of behaviour in effective altruism and existential risk circles, especially of leading and powerful figures. I hope more scrutiny will create incentives to behave better to avoid bad publicity. I have in mind roughly how good journalism can hold people with power accountable (I do not claim my essay is any kind of journalism). I hope more people, perhaps including journalists, will look into the broad kinds of behaviours I describe in this essay (not just the specific things I have mentioned). I have merely noted a few things that tell me that, in some cases, fishy things appear to be going on, and, in other cases, fishy things are happening. Unfortunately, an effect of me writing this text may be that people merely become better at hiding problematic behaviour. For example, I do not expect that people will tell me about new secret deals in effective altruism or existential risk circles, or about someone ghostwriting for person X, or about money changing hands perhaps partly in return for favours. I expect many problematic things to continue to go on behind the scenes.